“You’re really pretty for a Black girl.”

“Is that your real hair?”

“You have your dad in your life?”

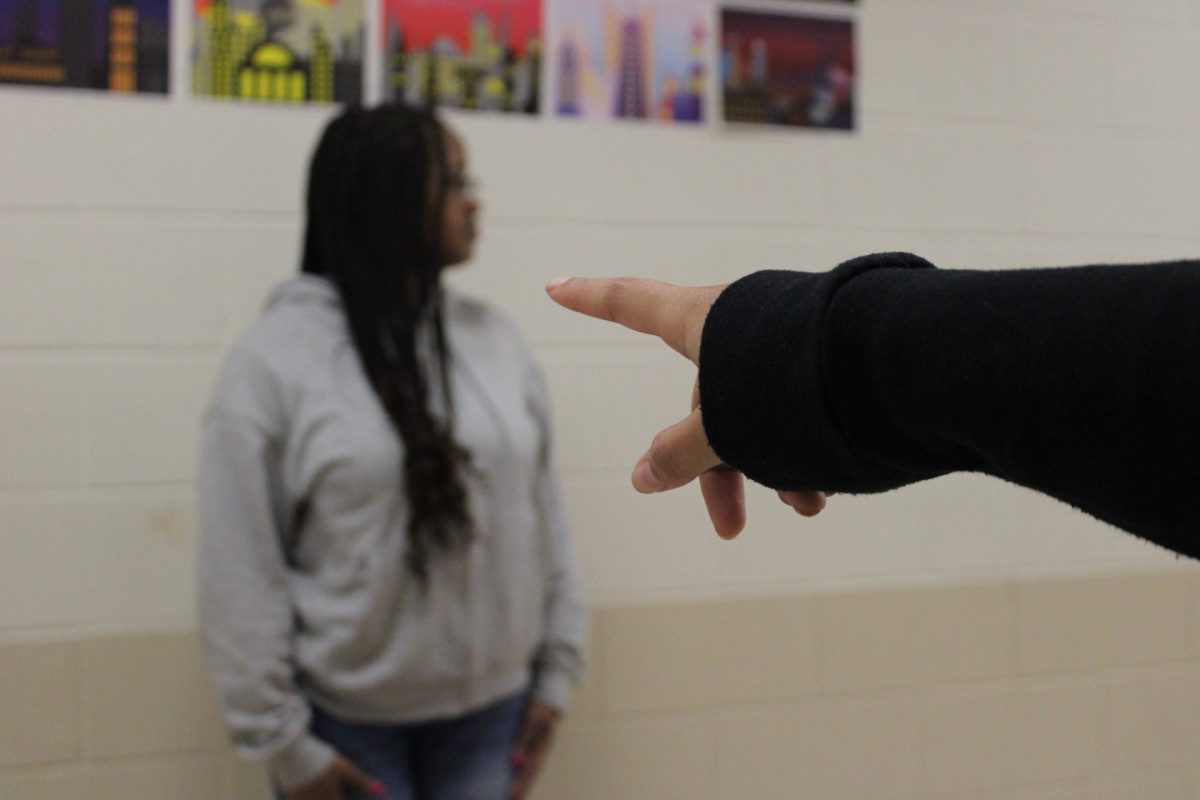

Hearing these things being said to us doesn’t comfort us in any way possible. So, why do non-Black individuals feel as if it’s okay to mention them?

We all know about the blatant racial slurs, threats, and remarks that are made towards Black individuals, but statements that are said that “come out wrong” or “backhanded” compliments, otherwise known as micro-aggressions, are also a part of a racial stigma that should be discussed.

According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the mention of these racial comments have stemmed from as early as the height of the Trans-Alantic Slave Trade. They were used to justify the business of slavery, which caused us Black people to be labeled as “submissive”, “lazy” or “unprincipled.”

The participation in this “trend” has been something that has been relevant for many years but also something that society has pushed back into the background to invalidate the feelings of Black people.

Hair

With these comments being subtle (not really) forms of racism, there are many conceptions that come along with it.

One of the most common ones that I have seen is “I didn’t know your hair could even do that.” While the intention probably was a compliment to the protective styles that Black people implement, it comes off as a superiority mindset.

Society has been, and continues to be, more familiar with nothing more than straight and smooth hair since the 19th century. Anything that wasn’t that, was deemed as “unprofessional,” “flamboyant” or made it “hard to concentrate.”

In response to nerves from not being accepted, Black women found and implemented techniques like perms, hot combs, and silk presses, while Black men either kept their hair fairly short or just shaved their head as a whole to fit the “beauty standard.” As time progressed, the acceptance of hair styles, with help from the C.R.O.W.N Act, have become more prevalent within the community, in which styles like cornrows, box braids, mini-twist, and many more, could be worn comfortably without judgment or backlash.

While society has been more open to the idea of allowing hairstyles to be worn without any repercussions, comments like “Make sure your hair is neatly kept.” and “I didn’t know your hair could even do that!” makes it seem as though the styles are still threatening to the societal norms of America, or as if our hair is inferior to theirs because it’s not as easy to manage.

Judson alum, Jeremiah Moore, comments on how challenging it could be to find job placement with hair like his.

“It’s always been my hair and the way that people judge me for it. For example, going to a job interview with twist in my head, versus a man who is, Caucasian descent, with long hair, but it’s straight. It’s like my appearance in hair is somehow a threat to them. They feel as if it might jeopardize their company or that it isn’t professional for them,” Moore explained.

The discrimination of one’s hair is also a pivotal entry point into understanding the broader context of societal expectations and biases that shape perceptions of Black femininity.

Femininity within Black women

Black women have been a topic of discussion among many ethnicities for years, yet the recognition isn’t what one would perceive as good. Being told that they are “pretty for a Black girl” or “if only you were a little lighter” isn’t the compliment that one may think.

In actuality, it promotes the ignorant concept that there is, in fact, a beauty standard, and they don’t fit it. This eurocentric ideology has affected the mental and emotional well-being of Black women in the context of relationships, ways of living and work habits.

It impacts the self-esteem of Black individuals, specifically Black women, and how they view themselves. It makes them feel smaller-than or subordinate. While they know that those comments aren’t true, having many opinions surrounding them can become a challenge to not believing what is being said.

Sophomore, D’Aziya Ellison, explains her thoughts on the hardship of being a Black woman in today’s society and not living up to society’s standard.

“It hurts because what makes me not as pretty as a white girl? It brings up my experience of me always being the second choice.” Ellison said.

With us hearing these comments so much, we start to unintentionally adapt these views in our culture. It makes us more of a target to stereotype and discriminate against, because we are fitting in the box that they are trying to put us in.

And just as societal beauty standards can impose expectations and pressures, the familial dynamic within the Black community often harbors their own set of prejudices and stereotypes.

Black family dynamics

There are many tiresome tropes that surround Black families, most common being the “baby momma/daddy drama”, single Black parent, the “always misbehaved children”, and the “angry Black woman” .

The thing with these narratives is that they aren’t necessarily true within the Black community. Most of these started within the time period of slavery. Since slaves weren’t allowed to legally become married and were at constant instability within placement and families, it fueled many of the single parent households, “baby momma/daddy” drama, and “angry Black women” narratives.

In a 2013 CDC study about Fathers’ Involvement With Their Children, it stated that seventy percent of Black fathers who live with their children were more likely to have bathed, dressed, changed or helped their child with the toilet every day, than fathers of different races. The study also found that seventy-two percent of Black fathers talk with their children about their day over the phone multiple times a week, whether or not they live in the household.

“Your kids are so well behaved!” or “He’s all of their dad?” is what my parents hear multiple times a day from non-Black individuals.

Growing up, both of my parents have always been together, along with my dad being a constant in my life. When going out with him and any of my siblings, we are always side-eyed and seen as circus entertainers because we are so well behaved, like that shouldn’t be standard.

We would also get many raised-brows because apparently it’s shocking to see a Black man actually take care of his children. But he has always provided for me and my siblings, along with my mom, despite the “absentee father” stereotypes that surround the Black community.

“She [my mother] would never have to make me be a parent because I was going to be there regardless. But also, I never wanted you all to call me by my first name and mean it. I never wanted to answer the questions, ‘Where were you?’ or ‘Why weren’t you there?’” explained my father, Trumaine Cook.

Yes, our culture does take on some of these stereotypes, but we can’t deny the fact that other culture groups do it as well. There shouldn’t be a specific stigma against our people, just because it’s publicized for us more than others.

Be the change

By shedding light on some of these layers of discrimination, I try to help straighten out the web of biases and stereotypes that hinder the progress that our community has made. Exposing these microaggressions is essential in educating others, dismantling systemic discrimination and the strive towards a more equal society.

Racism has been very prevalent in America, but helping to educate others can contribute to the change of that narrative. Be a part of that change.