Advertisements are entirely unavoidable in this day and age. You could have the premium subscription of every online service, and still see advertisements in the form of billboards, paid sponsorships or even by word of mouth. They take up a considerable amount of space in our daily lives, and society has managed to tune them out.

Known intellectual and Philosophy professor Noam Chomsky notes in his documentary, Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (1992), that he could go to a baseball game in his youth and not see an advertisement— his youth being 1930’s-40’s America.

This raises the question of when the excessiveness of advertising began.

Origins and implications

An early example of advertisements can be seen in 3,000 BC when Egyptians used papyrus to create posters, an early form of billboards. One preserved advertisement promoted a weaving shop, and doubled as a poster for a missing slave.

Chinese poems from the 11th to seventh century B.C.E. have been translated to reveal candy sellers attracting clients by playing on bamboo flutes. Asia basically created jingles before the first paper advertisement even hit the West.

The first paid advertising space in the Americas can be seen in 1704, influencing potential businesses to advertise their goods for a small fee. Two weeks after the initial offer, the Boston News-Letter printed the very first paid newspaper advertisements “land for sale and a cry for help about misplaced anvils.”

Though not exactly reminiscent of targeted ads we see on our phones today, this began a precedent of advertiser-funded journalism. Instead of subscriptions paid for by the consumer, newspapers created adspace to make content accessible for people.

This in turn also boosted profits for newspapers who still take subscriptions at a discounted price, while still contracting advertisers. The very first zero subscription newspaper was published in 1831, known as La Presse in Paris, France as reported by Oldest.org

The implications of cutting articles to fit in more advertising space has been experienced first hand by notable editor and journalist of Deputy Views, Jillian Kaplan. In Kaplan’s October 2023 article “Newspapers: your advertisements are a problem,” Kaplan discusses the problematic nature of advertisements as she laments, “Distracting advertisements usually take up a disproportionate portion of multiple pages.”

The introduction of paid space essentially removed some of the creative liberties and opportunities journalists had prior to ad space. Not only that, but news became a propaganda tool due to the focus on consumer influence.

Ads only continued to get more obnoxious over time. Ethan Zuckerman, an American blogger and internet activist, created the very first pop up ad for his web-page. His original idea was to let brands influence consumers without being associated with the website the advertisement is embedded in. He has since apologized for the existence of his creation.

“The fallen state of our internet is a direct, if unintentional, consequence of choosing advertising as the default model to support online content and services,” he shared.

Zuckerman himself wrote the code that launches a window, and runs an ad over the page. “I’m sorry. Our intentions were good.” Zuckerman announced in an interview with Forbes.

Originally, advertisements were not targeted, and generalized to just get a product out. Today, it’s evolved into a data farm targeting the most likely consumer.

Creation of cookies

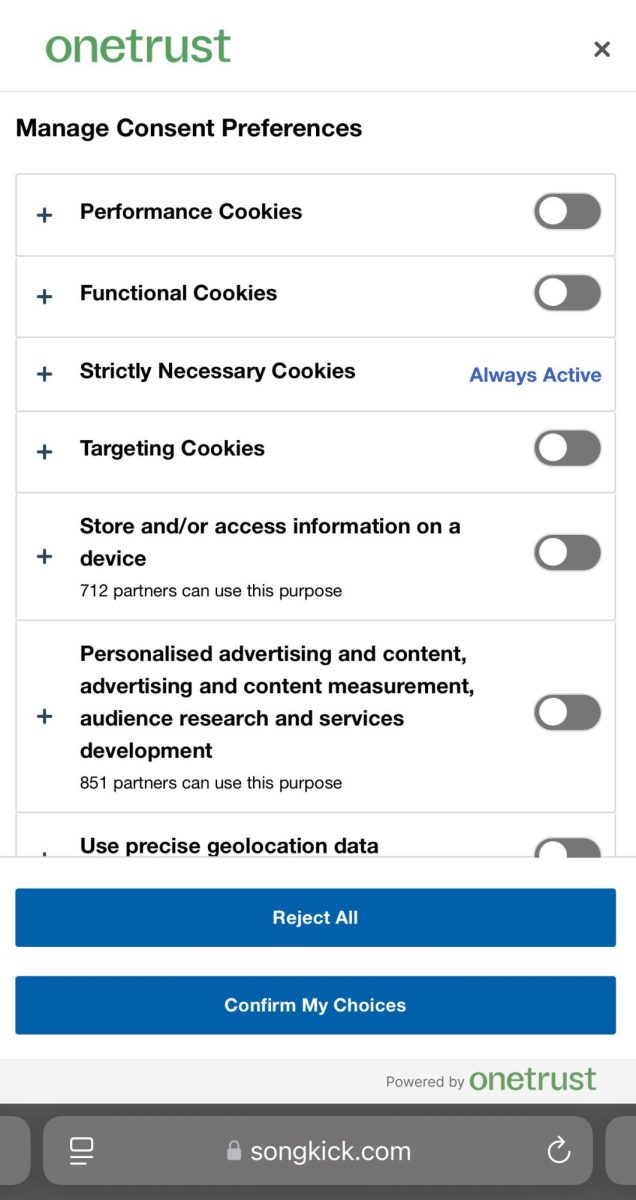

Every action on the internet is tracked by a genre of companies named data brokers. These data brokers take the data of your internet surfing and sell it to companies in order to personalize the ads you see.

According toNPR.com, in 1994 the very first cookie was created by Lou Montulli in order to allow websites to recognize users and maintain their same browsing session even after closing the tab. He collaborated with another computer programmer, John Gianandrea.

Though initially designed to aid users in their website usage, the cookie evolved into an extremely profitable business for marketing. Advertisers began using cookies to track users past just the browsing session within the website, and data brokers would use that same data to sell back to other advertisers.

Simple interactions on your smartphone can put you into “audience segments” for data brokers to sell and advertisers to buy. A Google search, a double tap on Instagram (owned by Meta) can be categorized into patterns which in turn lead to the type of advertisements you see. This is done so much, in fact, that Google was just recently caught collecting their users’ sensitive data without explicit consent for advertising purposes.

In an investigation reported by The Wire, a spreadsheet revealed that Google’s Display & Video 360 was using sensitive data from their users to sell to advertisers. Though their consent was not explicit, the promise in their terms and conditions to not abuse the information given was.

Before The Wire could analyze the information on the spreadsheet, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties obtained the document and realized Google was targeting users exclusively with health conditions and other specific criteria.

Google spokesperson Eric Walsh divulged the intricacies of the terms users agree to.

”Our policies do not permit audience segments to be used based on sensitive information like employment, health conditions, financial status, etc,” Walsh stated.

Walsh says this, but Google itself had audience segments named “Individuals likely to have a cardiovascular condition” and “parents of children likely to have a respiratory disease, like asthma” on this confiscated spreadsheet.

Personal information such as that seems insignificant, but it only gets more horrifying. Out of the 33,000 individuals’ information, there were also government officials being put into categories. Some include “specifically in the field of national security” and “decision makers.”

The implications of that data being sold to a company with harmful intentions are alarming. Justin Shermman, CEO of Global Cyber Strategies, expresses this in an interview with The Wire.

“This is exactly the kind of seemingly obscure data that would pique a foreign adversary’s interest,” Shermman stresses. “It speaks to something that could potentially be exploited in an intelligence context.”

In theory, the data is harmless in the right hands. But the data being given to a company with malicious intentions could mean true harm to users in the form of blackmail, stalking, harassment and public shaming.

In a declassified government document released in June 2023, written in 2022, The United States Office of National Intelligence noted that data could be combined to reverse engineer the identities of initially anonymous information. Cookies and other tracking services that companies like Google use might mean more targeted ads, but also may become a threat to national security.

The U.S. government has little to no regulations on the use of data, but other countries are more privy to the increasingly invasive technological advancements.

What is being done?

The internet is a generally new technology. According to the University System of Georgia, it’s only been around since 1993. Governments have only had 32 years to update their laws, and with the diversity of populations, plus the many ways laws can be interpreted, it’s a slow process to write laws inclusive to everyone.

The fastest law making can be seen in mostly European countries due to the less diverse population and small size of territories compared to their American counterparts. In fact, in 1973, Sweden took proactive measures to protect its citizens’ private data with the rise of computerized databases.

Sweden’s Data Act of 1973 created the Data Inspection Board, and required organizations to acquire explicit consent from users before collecting data. Reported by Graham Greenleaf in his research paper, Countries with Data Privacy Laws – By Year 1973-2019, Sweden laid the groundwork for the rest of Europe to follow in its footsteps.

While the United States has been slow to create comprehensive data privacy laws, the European Union has been busy. In 2018, they implemented the General Data Protection Regulation, arguably one of the strictest privacy laws in the world.

The law requires companies to obtain consent from users to collect their data, and allows users the opportunity to delete all personal data collected. If a company violates these regulations, it can be charged hefty fines of up to 10 million euros, or 2% of their global turnover. These fines are not only paid to the government, but victims of a data breach could receive up to 25,700 euros if the leaked information led to serious consequences, as shared by the GDPR website.

Similarly, China has also taken steps to regulate how data can be transferred in and out of the country. The Personal Information Protection Law in 2021 focuses on national security and consumer protection in relation to their identifiable data. The University of Illinois states, “[PIPL is] similar in many respects to the EU GDPR but with its own unique requirements.”

The United States mostly operates on a patchwork of state laws, like California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). According to the California Department of Justice, users have the right to know about the personal information companies collect, to delete and/or opt out of selling or sharing of their information and to be treated fairly when exercising the previous rights.

The law California voters approved in 2020 is extremely thorough and effective on a state level, but unfortunately lacks federal level enforcement.

This haphazard collection of various privacy laws is only helping the companies who fight to bypass these laws in the first place. The disparity only highlights the need for better, more comprehensive and universal standards to prevent the exploitation of user data.

Ethical Consequences and Questions

There are two sides to the advertising debate. One side argues that targeted advertising helps consumers see more relevant products and services. The other side argues that the surveillance and data required for these personalized ads is too steep of a trade off to justify.

Unfortunately, both sides have a valid point. News websites and most free services, such as social media platforms, rely heavily on advertising to remain profitable. At the same time, people like consumer behavior specialist Jacob Teeny have reservations about the effectiveness of the highly targeted ads.

In an article with Kellogg Insight, Northwestern University’s newspaper, Teeny relays this thought process.

“If you’re scrolling and think, ‘Whoa, that ad is really tailored for me’- as soon as you have the metacognitive awareness, it starts to bring in the feeling of, ‘Oh, I think they’re trying to manipulate me.’” Teeny shares.

That is essentially what companies are doing: manipulating consumers in hopes that a freakishly specific ad encourages them to spend money on their services or product.

When overweight consumers see an advertisement about weight loss, they are more likely to react negatively to the ‘negative’ stereotyping, as seen in a study done by the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

The feeling of being judged not only backfires on advertisers; it raises ethical concerns as well. Is it truly ethical to advertise payday loans to a person in poverty or debt? Or, to target an advertisement for an ice cream shop towards a depressed person? Teeny asks, “Where do we draw the line?”

Psychological manipulation has been used by major advertisers since the 50s to influence consumers at their root emotions. Edward Bernays, generally seen as the father of public relations and propaganda, studied how emotions influence purchasing behavior. He was the very first to promote the idea that advertisers should sell their products based on emotional needs rather than rational decisions, according to the Museum of Public Relations.

On the basis of the work of Bernays’s uncle, famous psychotherapist Sigmund Freud, he influenced every crevice of our country’s history. While working for Beech-Nut packing company, he convinced 5,000 doctors to sign a statement recommending a protein rich breakfast. With his company, he advertised bacon and eggs as an American breakfast in the newspaper, allowing the Beech-Nut packing company to have their brand of bacon put in every grocery store in America. This Bacon Affair was thoroughly reported by GoBraithwaite.org

Another product Bernays famously marketed was the Lucky Strike cigarettes, which he nicknamed “Torches of Freedom.” In the 1920s, smoking was very taboo to women socially. In need of new consumers, the American Tobacco company hired Edward Bernays to stage a PR stunt.

Bernays’s stunt was pulled off during the 1929 Easter Sunday Parade in New York City. He hired fashionable women to publicly smoke, as a symbol of equality. He convinced women that buying and smoking cigarettes was helping their suffrage movement, while his actions were in the interest of his employer’s stocks. According to the Cultural Currents Institute, Lucky Strikes became an icon of the Feminist Movement.

Bernays’s books and practices were used to manipulate the German population into Nazism, and to convince Guatemalans that their democratically elected leader was a communist threat in alliance with the Soviet Union. His genius has been used for manipulation in harmless as well as extremely malicious ways, as highlighted in “Edward Bernays and the Rise of Public Relations” by Southern Georgia Edu.

In his book “The Principles of Propaganda,” Bernays writes, “The American Motion Picture is the greatest unconscious carrier of propaganda in the world today. It is a great distributor for ideas and opinions.”

Bernays also created a concept of dopamine loops now most commonly used by social media platforms today. Highly personalized advertisements on apps like TikTok rely on likes, shares and engagement that in turn adjust future ads to maximize engagement. This endless scrolling of short form content, almost indistinguishable to advertisements encourages addictive behavior to the likes of gambling, as seen in an article by the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation.

The blurring of the advertising and content line makes it harder for users to recognize when they’re being marketed to, further enhancing the unethical manipulation of users across all social media platforms.

Ethically, more companies should realize their marketing might be good for business, but is entirely too invasive to remain safe.

At what cost does the convenience of targeted ads come? If left unchecked, how much longer until the internet and news is one big meticulously curated propaganda machine where every action is monitored and monetized to best fit a company’s interest?

In conclusion, advertisements are too much: in their frequency, their content and their strategies to be the most effective. Decades of negligence have gotten us to this point and individuals must take steps to protect their information by paying attention to their privacy settings, advocating for stronger privacy laws and installing ad blockers to prevent unethically promoted advertisements.