New Voices movement aims to give student journalists full free press rights

Editor Izabella De La Garza takes a look at the New Voices Texas, “a student-powered grassroots movement to give young people the legally protected right to gather information and share ideas about issues of public concern.”

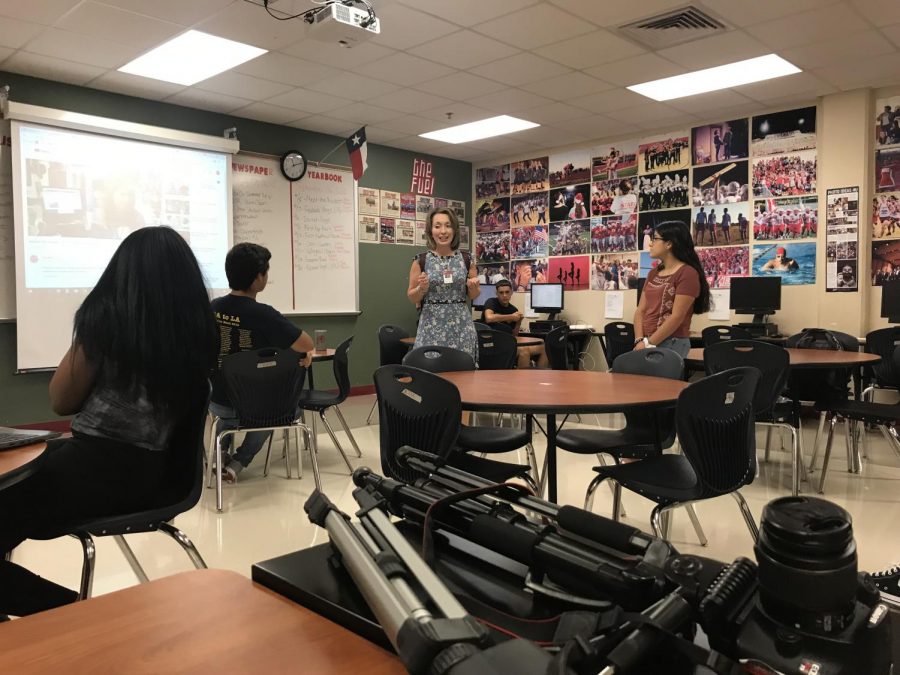

Photo By: Mr. Cabrera

Dr. Ball, Judson Superintendent, talks with The Fuel staff about her goals as her first year leading Judson ISD and the needs of the students.

Our nation glorifies our freedoms, especially those of our First Amendment. They are the freedoms of religion, petition, assembly, press, and speech. Even with the pride this country claims in the freedom of speech and press, some states allow school administrators to essentially censor student journalists’ articles, investigations, and research.

In 1988, articles written by student journalists at Hazelwood East High School were reviewed by their principal. They were told to not be published the article. A few of the students decided to react by taking the school district to court as they felt their first amendment rights were being infringed. The Hazelwood vs Kuhlmeier case made it all the way to the US Supreme Court. According to USCourts.gov, the Court ruled that the principal’s actions did not violate the student’s free speech rights. The Court noted that the paper was sponsored by the school, and as such, “the school has a legitimate interest in preventing the publication of articles that it deemed inappropriate and that might appear to have the imprimatur of the school.”

This decision paved the way for student publication censorship, but it has also set the ground for something much larger: New Voices.

According to NewVoicesUS.com, the movement is “a student-powered grassroots movement to give young people the legally protected right to gather information and share ideas about issues of public concern.” The movement was created by the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), a non-profit and non-partisan legal agency whose function is to support, educate, and provide for student journalism organizations. Through the campaign, advocates have collaborated to push legislation and establish state laws that reverse the ruling of Hazelwood vs. Kuhlmeier.

Senior Joe Leasure, third-year yearbook staff member

These laws prevent school administrators from censoring their student journalists. Student journalists would be able to write hard-hitting editorials, exceptional and possibly controversial news, and perform more in-depth investigations without the concern of having anyone prohibiting them to do so. They would still have to follow the appropriate ethical and morals guidelines of a good journalist. At the moment, only 14 states have a New Voices legislation: Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.

Texas currently has a New Voices movement, but it has only become more known since this past spring. The idea of a New Voices Act was brought into legislation in 2017 but never reached committee.

If Texas were to pass New Voices legislation, it would drastically change the standard for student publications, bringing a great opportunity for the involvement of another voice, and make news even more attainable for students by students.

“If we didn’t have the idea of censorship, or bias, or malicious intent, or anything, basically the idea of just letting truth ring out – I mean think about the understanding everybody could come to and the decisions that everybody can make on their own,” Texas Association of Journalism Educators (TAJE) President Margie Raper said.

In Burlington, Vermont, the Burlington High School student newspaper staff, The Register, recently covered a story involving one of the school’s counselors being fired. With the state’s New Voices legislation, the students had no concern about the story being censored. They were told by their principal to remove the story.

“We were frustrated, because everything we had published was public information, and the community has a right to know what goes on in our school,” The Register co-editor and senior Nataleigh Noble said.

The story was re-uploaded as the law protected their right to post it.

“We wrote one article that got censored and that left us feeling frustrated and confused. To have the possibility of that happening to every article I write would be so stressful and difficult to manage,” The Register co-editor and junior Jenna Peterson said.

As displayed in Vermont, their New Voices legislation allowed students to bring real news to their communities. Even when the administration tried to hold them back, they had a law to support them and their freedoms.

“It is frustrating that we have these kinds of censorship because they don’t know what we’re doing in our classroom and they stereotype or label journalists based on negative attitudes, rather than really investigating of what we are doing,” Raper said.

What makes New Voices even more powerful is that it is greatly fueled by the persistence of the students who are determined to get the rights they know they should have.

“This is what’s going to make this movement be very, very successful, is the student voices of it. That we as teachers, we cannot lead this charge. It has to be you guys,” Raper said.

Many have the concern that if the students’ voices were to lose the restriction, it would cause conflicts.

“That’s why advisors do what we do. We’re there to guide you, mentor you, coach you through the process, and help add perspective,” Raper said.

Mr. Pedro Cabrera, the publications adviser at Judson, is on the board of the Texas Association of Journalism Educators and is fully supportive of the New Voices movement.

“It’s like a gut punch when students get censored,” Cabrera said. “We have dealt with [prior review] on our staff. It creates a sense of self-censorship among student journalists. They want to discuss things that are important to them and the community. They want to report the news. But if they feel that they will be pushed back, because whatever they write is deemed ‘inappropriate’ or ‘controversial,’ even though it is news, then it is never reported or discussed. That isn’t journalism. That isn’t teaching them journalism.”

In a world full of so much to write about, inform people of, express opinions on, and investigate, even student journalists need the option to do just that. Just because student journalists are young does not mean they should be denied the same rights a professional journalist has. They are trying to, if not actually, do the same thing – to express themselves professionally and let the community know what they feel they should.

“I believe that journalists are invaluable to every single community and schools are no exception. There are truths to be uncovered everywhere,” Noble said.

Because students’ rights of press and speech are being retained, there is a void in the public voice. Another perspective is losing its opportunity to be represented. If Texas legislation passes this law, the “new voices” of student journalists can be heard the way they should be – freely and fearlessly.

“Our democracy is built on this foundation of checks and balances, and everybody’s voice can contribute to truth and accuracy. And I think there’s no truer voice out there than that of a student,” Raper said.